‘Nine-tenths of the fallen women in London were once shop

assistants,’ Lord Brabazon said in 1883. Denise, the heroine of Zola’s famous

novel Au Bonheurs des Dames, certainly had a struggle to keep her morals

intact, and not seek extra ‘employment’. Even when they were probably innocent

of soliciting, shopgirls were looked down on as at least ‘cheap’. In Zola’s novel, some of the bourgeois women

think that the shopgirls are ‘all up for sale, the wretches, like their

merchandise’.

Industrialization and imports from the colonies, such as

India, saw the rapid growth in the amount and variety of goods coming from all

over the world, including fine materials, exotic fruits and fancy china.

Department stores and specialist shops sprung up throughout the country. Women

began to enjoy shopping for leisure, and they preferred to be served by young

women rather than men. Jessie Boucherett founded the Society for Promoting the

Employment of Women to promote women shop assistants. ‘She asked pointedly, “Why

should bearded men be employed to sell ribbon, lace, gloves, neck-kerchiefs,

and the dozen other trifles to be found in a silk mercer's or haberdasher’s

shop”?[i]

Many girls started to want independence, and a better career

than being a servant. Being a shopgirl was increasingly regarded as ‘respectable,’

and they received better wages than servants. Shopkeepers preferred to employ

girls and young women, because their wages were much lower than those of male shop

assistants. The wages were usually two-thirds or even half the amount that

their male counterparts received. It was also a cleaner and less physically

demanding occupation than factory work.

Unfortunately, many girls who got jobs working in shops didn’t

know what they were in for. Low wages were not their only problem. They often

had to work incredibly long hours from early in the morning until late at

night. Sometimes they worked until midnight on Saturday if they got Sunday off.

Understandably, they were usually too tired to go to church on Sundays. The

battle for a half-day on Saturday was a surprisingly long one. They also had to

pay fines if they breached any of the numerous rules. Whiteleys had over 100

rules.

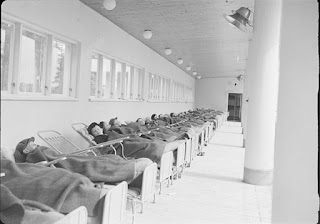

The shopgirls often had to live-in. This usually meant

living in crowded dormitories with nasty food, which they often had to buy. Many

received meagre breakfasts while they watched the shop managers and superior

staff eating bacon and eggs. Margaret Blomfield, the first woman Cabinet

minister in the UK, worked as a shopgirl when she was sixteen in a large draper’s

shop in Brighton. She was incredibly unhappy, sleeping in a bare crowded

dormitory, which was ‘incredibly hot in summer’ and ‘miserably cold in winter’.

It was so difficult to get a bath that to get a hot bath once a week the girls

had to run ‘at full speed for about half a mile’ to the public baths. Then they

only had a quarter of an hour to undress, bathe and dress before the assistant

ordered them out because the baths were about to close.[ii]

She was also incredibly scared when men knocked at the

ground-floor windows, and tried to pull them down during Race Week. They had a

struggle to slam and bolt the windows.

Margaret decided to join the Union, and spent time secretly

observing conditions. She wrote about them as Grace Dare. Vaughan Nash used her

reports in The Daily Chronicle, and they attracted the attention of Sir

John Lubbock, who used them to improve living-in conditions in The Shop

Assistant’s Act.

Conditions Improve

Even though the Coal Mine Act was passed in 1842, the first

committee on shop conditions only reported toa Parliament forty years later.

There were three committees, but nothing was done, because opposition remained

strong for three main reasons. Many thought that the State shouldn’t interfere

with working hours. Shopkeepers felt obliged to be at the mercy of the

customer, and the need for profits was difficult and competitive. Also, shop

assistants mostly didn’t want to join a union, because they felt that it was

beneath them.[iii]

A few acts of Parliament improved conditions, but it wasn’t

until the Shop Assistants Act of 1911 that a statutory half-day and a mandatory

weekly holiday were introduced. The next two acts of 1912 and 1913 shortened

the maximum weekly working hours, and made washing facilities mandatory in

every shop.

[i]

‘Association for Promoting the Employment of Women’, English Woman’s Journal,

vol.4, September 1859, p.57, quoted in Horn, Pamela and Annabel Hobley, Shopgirls,

The True Story of Life Behind the Counter, Hutchinson, London, p.45

[ii]

Horn, Pamela and Annabel Hobley, Shopgirls, The True Story of Life Behind

the Counter, Hutchinson, London, p.90

[iii]

Whitaker, Wilfred B. Victorian and Edwardian Shopworkers. The Struggle to

Obtain Better Conditions and a Half-Holiday. David & Charles Newton

Abbot, 1973, p.180